Moses and the Burning Bush, 1883 by John Martin

A particular pen on one’s desk is known among others by its distinguishing characteristics; these features being unknown would render the pen an unidentified member of its collective category.

“Grab a pen from my desk.”

“Which pen?”

“Any pen, they are all the same.”

In fact, varying sizes, colors, and unique scratches in lacquer set the objects apart. The recognition of each implement is dependent upon both its collective and individual identity. The object on the desk is known as a pen insofar as it shares essential features with other members of the pen category; the pen that I ask for is known by its distinctive presentation of these features. Likewise, I am known as a person insofar as I present the qualities of personhood; the person I am is known by what sets me apart from other persons.

As features relating to the collective category are observed to differ in expression, collective subcategories confer identities that are nested within that of the greater collective category, e.g., fountain and ballpoint as identities within the greater identity of pen. Further differences within the subcategories ultimately bring individual identities as categorization reaches its end, an epistemological limit corresponding to the depth of one's relationship with the existent being identified, e.g., long red fountain, short blue fountain, long blue ballpoint, short red ballpoint, short blonde man, tall ginger woman, etc.

“Hey, you!” I shout.

Everyone turns.

I am then more specific, “Sir!”

The men in the room continue looking while the women turn away.

More specific yet, “Short blonde man!”

The miliue dwindles.

“Mr. John Crumb!”

The man with whom I wish to speak remains facing me.

Thus, individual identity is obtained by existing in a relational state of otherness among fellow constituents of a collective category. Suppose the object were to know itself and its others.

“I am a pen, you are a pen.”

Suppose the object were alone.

“I am…What am I?”

The object's individual identity is redundant where other objects, which are essentially alike though ostensibly different, are not present to form a category and collective identity. It might be said that the subjective identity of I remains despite the sentient object's solitude. However, if identity as such depends upon the relation of two existents, one being set apart from the other, awareness of oneself as an I would be dependent upon the existence of some other I with which to relate. Therefore, whence comes I to the lonely?

Adam Naming the Animals, circa 1630 by Jan Brueghel the Younger

To be alone is unreconciled otherness. One is an other to his family, his neighbors, his environment, his god(s), and indeed himself. These relations confer particular identities to the self, e.g., son, friend, steward, worshipper, I, etc. Inter-category relationships arise from teleological dependency. The object on my desk is a pen, not the paper it stains; however, the identity of pen cannot be fulfilled without a surface to mark. Likewise, a being is not its environment, but it could not be without one.

Identities created in intra-category and inter-category relationships suffer upon the loss of either; there is a positive correlation between the degree of separation between identities within a relationship and the damage delt to them. A woman conceives a male child, creating the identities of mother and son within a family. The son is swept away by a rip current on a vacation to the coast. The woman that once nursed, nurtured, caressed, and cultivated the life she bore is bereft and bereaved of the apple of her I. A gardener is injured, leaving his garden unattended for some time. In the gardener's absence, the garden is overrun with weeds. It is no longer a garden, it is indiscernable from wilderness. How is one to act as a mother to a dead son or as a son to a gone father? What is a gardener with no garden or a garden with no gardener? Can one be a friend with only foes? How could the object on my desk without ink or a tip be written with as a pen? Thus, discordance with respect to inter-category and intra-category others damages the self as it is separated from that upon which and those upon whom its own identity depends within these relationships.

The issue extends to the self's subjective identity: If I am an I, and I am alone, how to know what I should be with no example except myself? As I stumble through my environment, of which I have limited awareness, I inevitably step on an unseen thorn. I encounter error, pain. As an ignorant lone wanderer, I do not know how an I should see because I am the only one. I am at odds with myself, confused, and afraid.

“Whoever has learned to be anxious in the right way has learned the ultimate.” – Søren Kierkegaard.

Søren Kierkegaard, 1902 by Luplau Janssen

Untowardness is recognized as the self perceives itself in unamiable relation to a valued other. Awareness of the self's untoward otherness poses two options: reconcile or rebel. Reconciliation occurs where the self is viewed and valued as a you in dependent relation to an intra-category other; in the case of an inter-category other, the self empathetically ascends or condescends to the higher or lower category, respectively. Rebellion is the self's rejection of an other for its identity.

Towardness – a state of concession and progression, active or passive and intentional or unintentional, with respect to a value.

Peace: Sense of towardness

Joy: Identification of towardness

Fulfillment: Identification with towardness

Untowardness – a state of transgression and regression, active or passive and intentional or unintentional, with respect to a value.

Anxiety: Sense of untowardness

Guilt: Identification of untowardness

Shame: Identification with untowardness

The (un)towardness experienced by the self corresponds to its position on the (un)towardness spectrum and the higher or lower status of the value in question.

“To see a world in a grain of sand / And a heaven in a wild flower, / Hold infinity in the palm of your hand / And eternity in an hour.” – William Blake

William Blake, 1807 by Thomas Phillips.

One attends to values, such as personal health, family welfare, political stability, social justice, etc., in a manner that falls on the spectrum of (un)towardness; values correspond to an identity of the self, and therefore to a relationship:

Personal Health - self and I

Family Welfare - son to mother, father to son, husband to wife, etc.

Political Stability - citizen to nation

Active and intentional towardness with respect to a value brings one’s greatest sense of peace, joy in acting, and fulfillment of identity. To conduct oneself in an untoward manner with respect to a value elicits anxiety to a greater or lesser degree depending on such action being active and intentional or passive and unintentional, respectively.

Suppose one highly values environmental cleanliness, they feel anxious at the thought of an other participating in a transgression against their high-status value. One's anxiety is greatest in the case of he or she intentionally acting in an untoward manner with respect to the value, e.g., littering. Recognizing the cause of anxiety, i.e., the act of littering, brings guilt in the case of personal culpability.

The relationship between the self and an other creates, orients, and animates one's identity; the anxiety experienced as a result of perceived untowardness with respect to a valued other compels and motivates value preservation for the longevity of the identity. Following an identification of that which one is, is not, and potentially could be in relation to a value, identification with the untoward state of neglecting value brings shame.

Adam and Eve Driven Out of Eden, circa 1868 by Gustave Doré

Religiously, Christian and Jewish sin, Buddhist akusala kamma, Hindu pāpam (पाप), etc., would be instances, patterns, or states of untowardness. The resulting anxiety and guilt, i.e., sense and identification of existential disconnection with the divine, is addressed via reconciliatory action toward fulfillment – redemption, salvation, enlightenment, Nirvana, moksha, etc.

In the Judeo-Christian cosmogony, awareness of untoward otherness is demonstrated by humanity's progenitors as they set themselves against that to which – the Other upon whom – they are ultimately dependent: “And the eyes of them both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together, and made themselves aprons.”1 Adam expresses the shame he and Eve experience in being exposed to the knowledge of good and evil, knowing what they are, are not, and could be; he says to God, “I heard thy voice in the garden, and I was afraid, because I was naked; and I hid myself.”2 To address their hopeless shame, i.e., identification with the Fall and the resulting existential untowardness, they attempt to cover themselves with foliage; God then clothes them in animal skins and turns them out of Eden.3 This scene, often thought a punishment, is best read as a mercy: To be juxtaposed with perfection in a state of imperfection is to find oneself within a category that is not his own, unreconciled, and alone.

God uses animal skins – implying the death of the animal – to cover Adam and Eve; the term for “atone” derives from the Hebrew kaphar (כפר) meaning “to cover.” Christian hermeneutic practice links this sacrifice with Christ's own. For the Christian, the pattern of reconciliatory towardness is embodied and fully realized in the being of Christ while rebellious untowardness is epitomized by Satan.4

“We shall be free. The almighty hath not built / Here for his envy, will not drive us hence; / Here we may reign secure, and in my choice / To reign is worth ambition though in hell: / Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven.” – Satan in Paradise Lost by John Milton

The Fall of Lucifer, 1866 by Gustave Doré

The Christian identity requires identification with Christ. In identifying with the manifest fulfillment of personhood, the embodied Logos (Word or Order), the Son of God, and the Second Person in Trinitarian theology, the Christian is brought into proper relation with the others within his own category of person, the inter-category others with which he shares an environment, and the Other upon whom the value of each self as an I, qua imago dei, is dependent. This identification is held as a soteriological imperative: “No man cometh unto the Father, but by Me,” says Jesus.5 Through reconciliatory identification, the Christian does not lose individuality nor is he conflated with the Other who is beyond category. Rather, in recognizing and accepting its dependent position, the self is given a new identity to embody.

The Rose Gives Honey to the Bees, 1629 from Medicina Catholica by Robert Fludd (first)

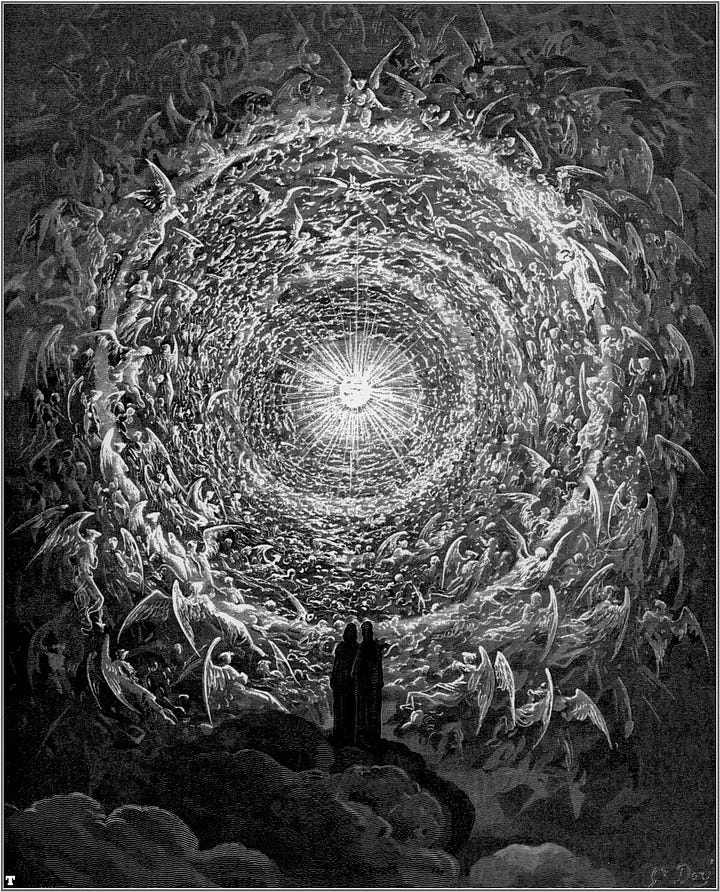

Dante’s Beatific Vision, circa 1868 by Gustave Doré (second)

Where an I is known, a you is present; indeed, “where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them,” says the Second Person.6 To identify with, see through, and live in the second person – to be a you to an other's I – is not a loss of individual identity but a recognition of the others and Other without whom the I would be unknown, cease to be.

Two I's affording proper depth perception, the self sees its own value clearly – I am a you because you are an I.” Jesus, the O/other as both God and man, admonishes against the self-destructive selfishness of stumbling through the wilderness with only the lone, near-sighted, and unreconciled I, “For whosoever will save his life shall lose it…whosoever will lose his life for my sake shall find it.”7

Qua Logos incarnate, Christ unites fact and value, is and ought, object and subject, self and I; the Other's condescension to and identification with humanity allows the self, others, and the Other to be known and reconciled. Thus, to actively and intentionally sacrifice one’s I for a new identity in, with, and through the O/other is to “love the Lord thy God” and “love thy neighbor as thyself”8 – You and I are for each other.

The Calling of Saint Matthew, circa 1600 by Caravaggio.

Reconciliation of relationship through the fulfillment, not negation, of identity is central to the New Testament, hence the name; many examples are shown of one's I being given new vision and identity by the light of the O/other, to wit: the respective encounters of Levi/Matthew, Simon/Peter, and Saul/Paul with Christ. Levi/Matthew, a member of the ill-regarded tax collector category, is beckoned from his occupation by Jesus to serve as a disciple.9 Simon, a fisherman whose name means “he has heard,” becomes Peter, meaning “stone” or “rock,” and is tasked with founding the church.10

Saul, a Pharisee “breathing out threats and slaughter against the disciples of the Lord” on a mission of persecution following the events of the Passion, falls to the ground as “there shined round about him a light from heaven.” He hears a voice say to him, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” The enlightened voice identifies itself, “I am Jesus whom you persecute.”11

Conversion of St. Paul on the Road to Damascus, circa 1865 by Gustave Doré

The blinded man, “trembling and astonished,” says, ‘Lord, what will you have me to do?” Christ instructs him to “arise, and go into [Damascus], and it shall be told you what you must do.”12 Saul, who “could not see for the glory of that light,” is led by the hand of his others that “saw indeed the light, and were afraid.”13 He is brought to Ananias, “a devout man according to the law,” who restores Saul’s sight and tells him that “God of our fathers has chosen you, that you should know his will, and see that Just One, and should hear the voice of his mouth.”14

The three aforementioned figures each encounter the O/other’s I, they see Christ in Jesus, the value in the person. They are found where and as they are, and shown where and who they could be. To see the Second Person, the you – the Other in the other – is to see who one is, is not, and could be. One sees that he knows himself as an I because the O/other is an I that knows him as a you. Therefore, “those with eyes to see and ears to hear” accept the quest of reconciling otherness. They beckon every I to turn from the lowly shadow of the self toward the light, the value, the you of the O/other, as they were beckoned: “Be not afraid…Rise up quickly…Follow me.”15

St. Peter Being Freed from Prison, circa 1617 by Gerard van Honthorst

The events of Peter’s persecution by Marcus Julius Agrippa (Herod Agrippa) as they are described in the Acts of the Apostles illustrate the battle waged within the repentant self between reconciliatory identity and rebellious identity, a daily scrimmage in the war erelong won by the O/other.

“Herod the king stretched forth his hands to persecute certain of the church…he proceeded further to take Peter…he put him in prison…intending after the passover to bring him forth to the people.”16 Peter, the archetypal disciple of the Second Person, is chained by a prideful king. As he sleeps, “an angel of the Lord stood by him, and a light shined in the cell.” Peter is awoken by the light, “and his chains fell off from his hands.”17 The king's prisoner goes free; once he has “come to himself,” he says, “Now I know of a truth, that the Lord hath sent forth his angel and delivered me out of the hand of Herod.”18

“Arrayed in royal apparel,” Herod Agrippa speaks to his others with “the voice of god, and not of a man.” He is then destroyed by the same light that delivers the apostle because “he gave not God the glory.” Peter’s persecutor is taken from himself, and given to the worms.19

Death of Herod Agrippa, circa 1703 by Jan Luyken (first)

The Wrestle of Jacob, 1855 by Gustave Doré (second)

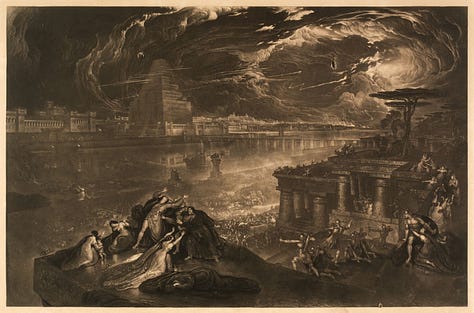

The Fall of Babylon, 1819 by John Martin (third)

Suppose my pen were to gain the knowledge of pen and not pen, deny its fellows, and proclaim its identity to be independent of the others in its family; it tosses its tip and spills its ink in stubborn refusal of being written with. The others could not see it as one of them; in search of a pen I would toss the unrecognizable object back in the drawer – “I know you not.”20 It would be unreconciled to itself, without purpose, without a name, alone.

As a confused and frightened tool, how to know what a good pen should be and do? A feather is dropped among the prodigal ballpoints to remind them,

“Know the writer as you are wielded in passion and bear his word with the ink that runs through you now, that once covered me.”

The Inspiration of Saint Matthew, circa 1602 by Caravaggio

Genesis 3:7

Ibid., 3:10

Ibid., 3:21

Isaiah 14:12-14

John 4:16

Matthew 18:20

Ibid., 16:25

Ibid., 22:39

Ibid., 9:9

Ibid., 4:18-20; 16:16-18

Acts 9:1-4

Ibid., 9:6

Ibid., 22:9-11

Ibid., 22:12-14

Matthew 13:16; Luke 2:10; Acts 12:7-8

Acts 12:1-4

Ibid., 12:7

Ibid., 12:11

Ibid., 12:21-23

Matthew 25:12

Thank you.

To support the work: buymeacoffee.com/vvegodvvin

Very interesting and I hope it didn't go over my head: Ones identity is in part defined by their relation to others, and that that relation should seek to be reconciliatory rather than a rebellious because the rebellious will leave one alone, without purpose or meaning?