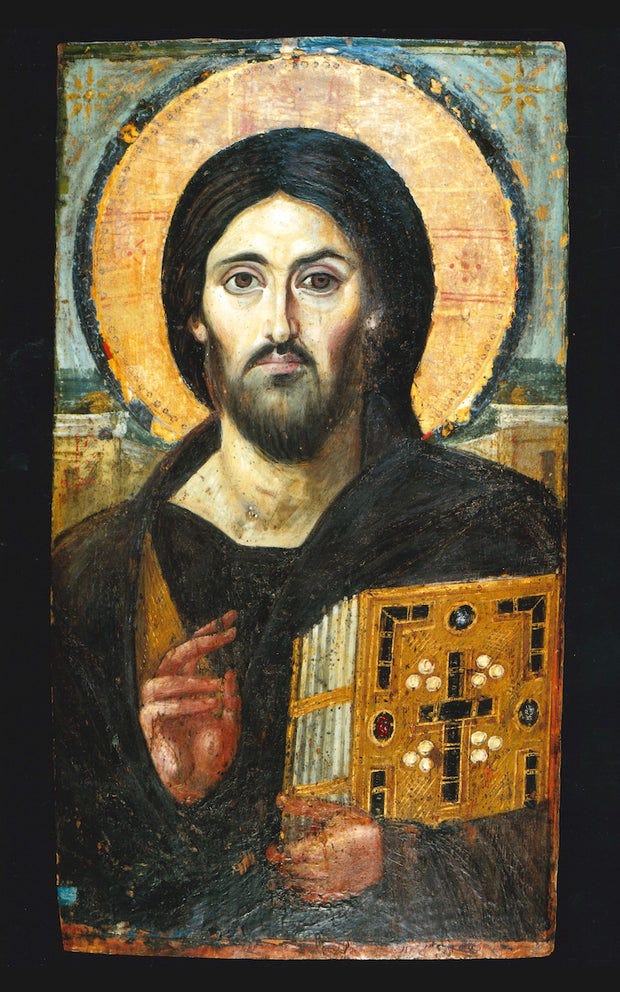

from Christ as Pantocrator, circa 6th Century AD by unknown artist

St. Catherine's Monastery at Mount Sinai in Egypt houses one of the greatest collections of Christian iconographic works. Among the most prized of these relics is a depiction of Christ as Pantocrator, or “ruler of all, all-powerful, all-mighty, etc.” Originally considered to have been a thirteenth-century work, following a process of research and cleaning conducted by Tasos Margaritof of the Byzantine Museum in Athens in 1962, it was concluded that the icon likely dates to around the middle of the sixth century.

An unknown artist produced this staple of Christian iconography in an encaustic manner, wherein hot wax is employed as a medium, as opposed to others such as egg yolk, for example. Art historians have come to associate the image with the art of Constantinople, particularly that which would have been displayed along and above the entrance to the Byzantine Sacred Palace known as the Bronze Gate.

As an Orthodox icon, the piece is laden with timeless Christian symbolism, certain colors are intentionally chosen to represent particular themes and ideas. Gold, a hue reserved for Christ alone, is used in the circular shape found behind the figure’s head, the book held by the subject, and in the inner lining of the purple garment he dons; as the “King of Heaven,” purple conveys Christ’s royalty. The aforementioned circle is acting as a halo; the book is likely meant to represent the Gospel or the Book of Life.

Of course, the most striking feature of this work is its asymmetry, another tool of symbolism. Either side of the figure’s face is noticeably quite different from the other, an intentional choice on the part of the artist. The right side of the subject’s face displays a soft compassion; conversely, the left could be said to convey an anger or disdain. One understanding of this decision is arrived at in considering a common motif within ecclesiastical art: the dual nature of Christ, i.e., as both man and God.

Another compelling assessment of this facial split is that it juxtaposes characteristics of the subject’s divinity: mercy and judgement. Indeed, as one examines the image further, this theme becomes increasingly clear. The figure’s right hand, of the “compassionate” side is performing a gesture indicative of the act of blessing. In the subject’s left hand, the Book of Life or the Gospel is held shut as Christ’s expression on the corresponding side communicates disapproval.

The term “communicates” is of great importance in appreciating the gravity of the message these symbols relate to the viewer. Christ’s gaze in this piece is penetrating, questioning, forgiving, and critical simultaneously; while it may be said that all art in some sense “stares back,” as an icon this image does so in a profound and multifaceted way. One could conceive of a choice being offered in Christ’s countenance. It is as though he were silently entreating the viewer to remember that which is said of he who sits at the right of the Father, so as not to be left behind, as it were.

Personally, this image engenders an awareness of self that is frightening, consoling, humbling, and ennobling in an instant, a sense one could imagine having been evoked in its first spectators several centuries ago. As such, the work is exceptionally well executed from an iconographic and artistic perspective for its efficacy in eliciting a profound aesthetic, and arguably spiritual, experience.

Bibliography

Apostolos-Cappadona, Diana. Visual Arts as Ways of Being Religious. In Frank Brown (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Religion and the Arts. Oxford UP, 2014

Christ Pantocrator, Palladion of the Monastery of Sinai. (n.d.). Mused. https://stcatherines.mused.org/en/stories/50/christ-pantocrator-palladion-of-the-monastery-of-sinai

Elkins, James. The Object Stares Back: On the Nature of Seeing. In Brent Plate (Ed.), Religion, Art, and Visual Culture: A Cross-Cultural Reader. Palgrave, 2002.